הבדלים בין גרסאות בדף "רצח הבלתי-אפשרי"

| שורה 3: | שורה 3: | ||

מאת מאט רוברטסון | מאת מאט רוברטסון | ||

| − | "רצח הבלתי אפשרי" פורסם לראשונה בשנת 1971 במגזין Mountain. [[ריינהולד מסנר]] יהפוך מאוחר יותר להיות מטפס ההרים ההימאלאי הגדול בכל הזמנים, אך בשנות השישים של המאה העשרים, הוא ואחיו גונטר היו ידועים כמטפסי הסלע הטובים באלפים. ריינהולד מסנר התפרסם במיוחד בפתיחת מסלולים נועזים על קירות שעדיין לא טופסו בדולומיטים, באיטליה. חלקם נחשבו עד אז קשים מדי או מסוכנים מדי לטיפוס ללא [[בולטים]]. עם זאת, מסנר האמין ברוח ההרפתקה והתגבר על הקשיים בעזרת מיומנות ונחישות, יותר מאשר בעזרת טכנולוגיה. | + | "רצח הבלתי אפשרי" פורסם לראשונה בשנת 1971 במגזין Mountain. [[ריינהולד מסנר]] יהפוך מאוחר יותר להיות מטפס ההרים ההימאלאי הגדול בכל הזמנים, אך בשנות השישים של המאה העשרים, הוא ואחיו גונטר היו ידועים כמטפסי הסלע הטובים באלפים. ריינהולד מסנר התפרסם במיוחד בפתיחת [[מסלול|מסלולים]] נועזים על קירות שעדיין לא טופסו בדולומיטים, באיטליה. חלקם נחשבו עד אז קשים מדי או מסוכנים מדי לטיפוס ללא [[בולטים]]. עם זאת, מסנר האמין ברוח ההרפתקה והתגבר על הקשיים בעזרת מיומנות ונחישות, יותר מאשר בעזרת טכנולוגיה. |

| − | הוא התנגד מלכתחילה ונקט עמדה בלתי מתפשרת נגד השימוש בבולטים כדי לאבטח [[פייס|פייסים]] ללא [[חריצים]], מאחר שהוא חש שבולטים הם דרך מלאכותית להקטין את הקושי ובכך ההם הורידו מחשיבותו של ההישג של טיפוס קירות כאלה.הוא | + | הוא התנגד מלכתחילה ונקט עמדה בלתי מתפשרת נגד השימוש בבולטים כדי לאבטח [[פייס|פייסים]] ללא [[חריצים]], מאחר שהוא חש שבולטים הם דרך מלאכותית להקטין את הקושי ובכך ההם הורידו מחשיבותו של ההישג של טיפוס קירות כאלה. בעיניו היתה חשיבות גם לכך שלא הכל יטופס, כך שגם למטפסי הדורות הבאים יישארו אתגרים "בלתי אפשריים" איתם יוכלו להתמודד. אם כל אחד עם מקדחה יוכל "להנדס" דרכו במעלה הקיר ללא כל מיומנות, אולי לא יהיו עוד אתגרי טיפוס למטפסי העתיד. היום, לאחר 37שנים, נושה זה נשאר מוקד לויכוחים ערים, כאשר מרבית מטפסי הצמרת מסכימים שבילוט מופרז הורס את רוח ההרפתקה. המטפס הבלגי קלאודיו ברביה התנגד גם הוא לבילוט ופתח את "המסלול של הדרקון" (Via Drago) כהצהרה כנגד הבילוט בכל מחיר. |

<div align=left> | <div align=left> | ||

| − | + | [[image: Via del Drage.jpg|center]] | |

| − | + | אמיליו קומיצי (Emilio Comici, 1901-1940), היה מטפס איטלקי מפורסם שהשלים מסלולים רבים בדולומיטים, ביניהם Via Comici, על הצד הצפוני של ה-Cima Grande di Lavaredo. המסלול, שנפתח ב-1934 הוא קו ישר למדי, החוצה קיר עצום בגדלו שנחשב בלתי אפשרי עד אז. גם היום הוא נחשב אחד מ"[[ששת הקירות הצפוניים]]" הגדולים של האלפים (עם האייגר, הגראנד-ז'וראס, הדרו, המטרהורן ופיצו-בדילה). קומיצ'י התפרסם בזכות הקונספט של "דירטיסימה" (direttissima): מסלול ישר העוקב אחרי | |

| − | + | Emilio Comici (1901-1940) was a legendary Italian climber who completed many important first ascents in the Dolomites, including the Via Comici on the North Face of Cima Grande di Lavaredo. The Via Comici is a very direct line up a huge wall that was considered impossible before this climb was completed in 1934. Still today it is considered one of the “Six North Faces” of the Alps. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Comici is also famous for the concept of the “direttissima” as a direct route up a wall that follows the imaginary path taken by a drop of water falling from the summit of the mountain. This “falling drop of water” path represents a perfectly straight line from the bottom of a wall to the summit of a mountain. (The Italian word direttissima has become commonly used in English as a climbing term for direct line up a wall; the more traditional English word plumbline, meaning a perfectly vertical line, is also used by Messner.) As an aesthetic ideal for climbing new routes on big walls, the direttissima can be seen to represent perfection. | |

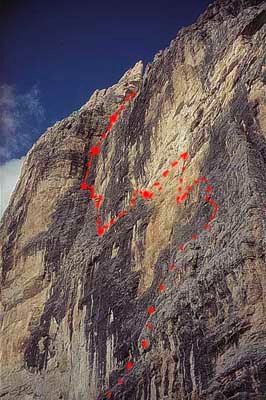

[[image: Via Comici.jpg|center]] | [[image: Via Comici.jpg|center]] | ||

גרסה מ־07:35, 13 בינואר 2008

הקדמה

מאת מאט רוברטסון

"רצח הבלתי אפשרי" פורסם לראשונה בשנת 1971 במגזין Mountain. ריינהולד מסנר יהפוך מאוחר יותר להיות מטפס ההרים ההימאלאי הגדול בכל הזמנים, אך בשנות השישים של המאה העשרים, הוא ואחיו גונטר היו ידועים כמטפסי הסלע הטובים באלפים. ריינהולד מסנר התפרסם במיוחד בפתיחת מסלולים נועזים על קירות שעדיין לא טופסו בדולומיטים, באיטליה. חלקם נחשבו עד אז קשים מדי או מסוכנים מדי לטיפוס ללא בולטים. עם זאת, מסנר האמין ברוח ההרפתקה והתגבר על הקשיים בעזרת מיומנות ונחישות, יותר מאשר בעזרת טכנולוגיה.

הוא התנגד מלכתחילה ונקט עמדה בלתי מתפשרת נגד השימוש בבולטים כדי לאבטח פייסים ללא חריצים, מאחר שהוא חש שבולטים הם דרך מלאכותית להקטין את הקושי ובכך ההם הורידו מחשיבותו של ההישג של טיפוס קירות כאלה. בעיניו היתה חשיבות גם לכך שלא הכל יטופס, כך שגם למטפסי הדורות הבאים יישארו אתגרים "בלתי אפשריים" איתם יוכלו להתמודד. אם כל אחד עם מקדחה יוכל "להנדס" דרכו במעלה הקיר ללא כל מיומנות, אולי לא יהיו עוד אתגרי טיפוס למטפסי העתיד. היום, לאחר 37שנים, נושה זה נשאר מוקד לויכוחים ערים, כאשר מרבית מטפסי הצמרת מסכימים שבילוט מופרז הורס את רוח ההרפתקה. המטפס הבלגי קלאודיו ברביה התנגד גם הוא לבילוט ופתח את "המסלול של הדרקון" (Via Drago) כהצהרה כנגד הבילוט בכל מחיר.

אמיליו קומיצי (Emilio Comici, 1901-1940), היה מטפס איטלקי מפורסם שהשלים מסלולים רבים בדולומיטים, ביניהם Via Comici, על הצד הצפוני של ה-Cima Grande di Lavaredo. המסלול, שנפתח ב-1934 הוא קו ישר למדי, החוצה קיר עצום בגדלו שנחשב בלתי אפשרי עד אז. גם היום הוא נחשב אחד מ"ששת הקירות הצפוניים" הגדולים של האלפים (עם האייגר, הגראנד-ז'וראס, הדרו, המטרהורן ופיצו-בדילה). קומיצ'י התפרסם בזכות הקונספט של "דירטיסימה" (direttissima): מסלול ישר העוקב אחרי

Emilio Comici (1901-1940) was a legendary Italian climber who completed many important first ascents in the Dolomites, including the Via Comici on the North Face of Cima Grande di Lavaredo. The Via Comici is a very direct line up a huge wall that was considered impossible before this climb was completed in 1934. Still today it is considered one of the “Six North Faces” of the Alps.

Comici is also famous for the concept of the “direttissima” as a direct route up a wall that follows the imaginary path taken by a drop of water falling from the summit of the mountain. This “falling drop of water” path represents a perfectly straight line from the bottom of a wall to the summit of a mountain. (The Italian word direttissima has become commonly used in English as a climbing term for direct line up a wall; the more traditional English word plumbline, meaning a perfectly vertical line, is also used by Messner.) As an aesthetic ideal for climbing new routes on big walls, the direttissima can be seen to represent perfection.

However, as Messner points out, the desire to create “perfect” new routes may encourage ambitious climbers to “force” the way up climbing routes that are not natural, because the natural line of a climbing route (also called the “line of weakness” of the mountain) is seldom a direct line to the summit. Bolts enable the artificial “conquering” of a line, by climbers not able to climb it by natural means. If a direct line is too difficult to climb by natural (non-bolted) means, he states, it should be left for future climbers to aspire to. Without such unclimbed, “impossible” objectives, future climbers will not have the opportunity to raise their standards or to achieve greatness. “Impossible” routes, Messners says, are therefore an important part of climbing, and using technology (bolts) to “kill” these impossible routes destroys the opportunity for future generations to reach for great successes – or, equally important in Messner’s view, to fail with nobility.

In the 1960s rock climbers used pitons for protection, which (like cams and nuts used today) depend on finding cracks for protection. Climbing great slabs (large faces without cracks) was a skill that challenged both body and mind, because of increased risks of climbing large runouts. Routes with the largest and most difficult runouts have always been reserved for the top climbers of any generation; modern examples include the Bachar-Yerian of Tuolumne Meadows (Yosemite National Park), the hard routes on Gritstone in England’s Peak District (made famous in the movie Hard Grit), and the sandstone towers of the Elbesandstein area in Saxony (along the German-Czech border). In any of these areas, if bolts were added to the climbs it would immediately reduce the difficulty and therefore the accomplishment of climbing these routes. Local climbing culture (and, in the Elbesandstein, even local laws) prohibit the addition of unnecessary bolts, in order to maintain the challenge and opportunity for climbers to learn and excel.

The debates on bolting alpine faces in the 1960s are similar to today’s bolting issues. A universal debate that now takes place in climbing areas around the world is the discussion about bolting sport climbing routes. Sometimes the debate continues for decades. Rock type and quantity of cracks (which could be used for traditional protection) will sometimes determine the answer, but more common is the local climbing culture and the voices of opinions. Some appreciate tradition and adventure, others point out that bolts are useful and necessary for improvement in climbing levels. It becomes nearly the same argument as took place in Messner’s day, and not surprisingly he still speaks out against bolts and sport climbing.

Are bolts still “the murder of the impossible?” Is bolting of modern sport routes destructive to adventure, to our activity, to our opportunity to excel? Or is bolt-protected climbing the way of the future, necessary for improving our technical abilities to make us better climbers? These are questions which will continue to raise discussion and debate for years to come.

The Murder of the Impossible

Reinhold Messner

What have I personally got against "direttissimas"? Nothing at all; in fact I think that the "falling drop of water" route is one of the most logical things that exists. Of course it always existed - so long as the mountain permits it. But sometimes the line of weakness wanders to the left or the right of this line; and the we see climbers - those on the first ascent , I mean - going straight on up as if it weren't so, striking in bolts of course. Why do they go that way? "For the sake of freedom," they say; but they don't realize that they are slaves of the plumbline.

They have a horror of deviations. "In the face of difficulties, logic commands one not to avoid them, but to overcome them," declares Paul Claudel. And that's what the 'direttissma' protagonists say, too, knowing from the start that the equipment they have will get them over any obstacle. They are therefore talking about problems which no longer exist. Could the mountain stop them with unexpected difficulties? They smile: those times are long past! The impossible in mountaineering has been eliminated, murdered by the direttissima.

Yet direttissimas would not in themselves be so bad were it not for the fact that the spirit of that guides them has infiltrated the entire field of climbing. Take a climber to a rock face, iron rungs beneath his feet and all around him only yellow, overhanging rock. Already tired, he bores another hole above the last peg. He won't give up. Stubbornly, bolt by bolt, he goes on. His way, and none other, must be forced up the face.

Expansion bolts are taken for granted nowadays; they are kept to hand just in case some difficulty cannot be overcome by ordinary methods. Today's climber doesn't want to cut himself off from the possibility of retreat: he carries his courage in his rucksack, in the form of bolts and equipment. Rock faces are no longer overcome by climbing skill, but are humbled, pitch by pitch, by methodical manual labor; what isn't done today will be done tomorrow. Free-climbing routes are dangerous, so they are protected by pegs. Ambitions are no longer built on skill, but on equipment and the length of time available. The decisive factor isn't courage, but technique; an ascent may take days and days, and the pegs and bolts counted in the hundreds. Retreat has become dishonorable, because everyone knows now that a combination of bolts and singlemindedness will get you up anything, even the most repulsive-looking direttissima.

Times change, and with them concepts and values. Faith in equipment has replaced faith in oneself; a team is admired for the number of bivouacs it makes, while the courage of those who still climb "free" is derided as a manifestation of lack of conscientiousness.

Who has polluted the pure spring of mountaineering?

The innovators perhaps wanted only to get closer to the limits of possibility. Today, however, every single limit has vanished, been erased. In principle, it didn't seem to be a serious matter, but ten years have sufficed to eliminate the word 'impossible' from the mountaineering vocabulary.

Progress? Today, ten years from the start of it all, there are a lot of people who don't care where they put bolts, whether on new routes or on classic ones. People are drilling more and more and climbing less and less.

"Impossible": it doesn't exist anymore. The dragon is dead, poisoned, and the hero Siegfried is unemployed. Not anyone can work on a rock face, using tools to bend it to his own idea of possibility.

Some people foresaw this a while ago, but they went on drilling, both on direttissimas and on other climbs, until they lost the taste for climbing: why dare, why gamble, when you can proceed in perfect safety? And so they become the prophets of the direttissima: "Don't waste your time on classic routes - learn to drill, learn to use your equipment. Be cunning: If you want to be successful, use every means you can get round the mountain. The era of direttissima has barely begun: every peak awaits its plumbline route. There's no rush, for a mountain can't run away - nor can it defend itself."

"Done the direttissima yet? And the super diretissima?" These are the criteria by which mountaineering prowess is measured nowadays. And so the young men go off, crawl up the ladder of bolts, and then ask the next ones: "done the direttissima yet?"

Anyone who doesn't play ball is laughed at for daring take a stand against current opinion. The plumbline generation has already consolidated itself and has thoughtlessly killed the ideal of the impossible. Anyone who doesn't oppose this makes himself an accomplice of the murderers. When future mountaineers open their eyes and realize what has happened, it will be too late: the impossible (and with it, risk) will be buried, rotted away, and forgotten forever.

All is not yet lost, however, although 'they' are returning the attack; and even if it's not always the same people, it'll be other people similar to them. Long before they attack, they'll make a great noise, and once again any warning will be useless. They'll be ambitious and they'll have long holidays - and some new 'last great problem' will be resolved. They'll leave more photographs at the hut, as historical documents, showing a dead straight line of dots running from the base to summit - and on the face itself, will once again inform us that "Man has achieved the impossible."

If people have already been driven to the idea of establishing a set of rules of conduct, it means that the position is serious; but we young people don't want a mountaineering code. On the contrary, "up there we want to find long, hard days, days when we don't know in the morning what the evening will bring". But for how much longer will we be able to have this?

I'm worried about that dead dragon: we should do something before the impossible is finally interred. We have hurled ourselves, in a fury of pegs and bolts, on increasingly savage rock faces: the next generation will have to know how to free itself from all these unnecessary trappings. We have learned from the plumbline routes; our successors will once again have to reach the summits by other routes. It's time we repaid our debts and searched again for the limits of possibility - for we must have such limits if we are going to use the virtue of courage to approach them. And we must reach them. Where else will be able to find refuge in our flight from the oppression of everyday humdrum routine? In the Himalaya? In the Andes? Yes certainly if we can get there; but for most of us there'll only be these old Alps.

So let's save the dragon; and in the future let's follow the road that past climbers marked out. I'm convinced it's still the right one.

Put on your boots and get going. If you've got a companion, take a rope with you and a couple of pitons for your belays, but nothing else. I'm already on my way, ready for anything - even for retreat, if I meet the impossible. I'm not going to be killing any dragons, but if anyone wants to come with me, we'll go to the top together on the routes we can do without branding ourselves murderers.